07 August 2019

The Scottish architect Charles Cameron is the great 'What If' of British architecture. A man of great imagination and skill, almost nothing remains of his work in Britain. He is instead revered in Russia as one of the greatest cultural exports of the 18th century.

Charles Cameron was born in Scotland in 1745, the son of a master carpenter and speculative builder to whom he was apprenticed, before moving in to the offices of Isaac Ware – a leading exponent of the Palladian style. Unlike his apprentice, Ware was born into poverty, working as a chimney sweep as a small boy and granted an education only when Richard Boyle, the third Earl of Burlington saw him drawing an elevation of Banqueting House on the pavement and recognised his raw talent. Boyle sent the boy to school, and then on to Italy where he set to drawing some of the great ancient buildings and monuments that were so integral to the neo-classical movement. Despite only designing a modest number of buildings, Isaac Ware created numerous drawings and celebrated treatises on architecture, making him an invaluable mentor for the young Cameron. Ware died only a year or so after Cameron entered his tutelage, but Cameron continued his master’s work by setting out to finish a new edition of Palladio’s, Fabbriche Antiche, commissioned by Lord Burlington. For this, he travelled to Rome, completing the drawings of Palladio so they matched the quality of Ware’s work.

Cameron returned from Italy in 1769 and published, 'The baths of the Romans explained and illustrated, with the restorations of Palladio corrected and improved', serving as a text book for neo-classical ornamentation and design. It was dedicated to Lord Bute whose patronage Cameron hoped to secure. It was re-issued in 1774 and 1775, an indication of its success. The book was a model of Enlightenment scholarship and had a strong neo-classical bias.

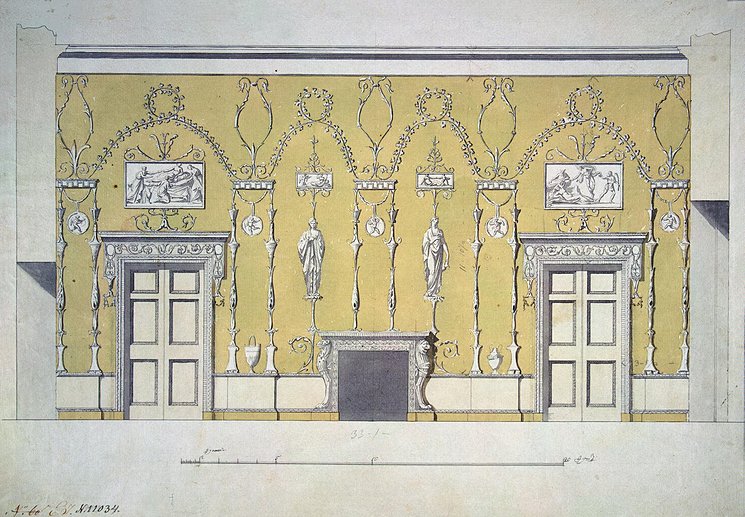

It's evident that Cameron had yet to begin his career as a fully fledged architect. Cameron’s only known architectural project in Britain was a house at number 15 Hanover Square, London. The house was built by his father for the Whig MP Jervoise Clarke. This project enabled him to demonstrate his ability to design neo-classical architectural interiors after the example of Robert Adam. Only one drawing from this project is known to exist, depicting an elaborate ceiling for a dining room. The sculptor and carver Thomas Carter supplied the chimneypieces and marble statuary for this project, a man also known to be a champion of Charles Cameron’s abilities; having sponsored him for a district surveyorship position in Middlesex. Cameron never attended his interview; perhaps as he had a grander role in mind.

Charles Cameron (1746-1812), No. 15 Hanover Square, Design for the Dining Parlour ceiling for Jervoise Clarke, 1770-75, Photo: © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

However his success as a London architect of great promise was cut short when his father - to avoid bankruptcy - sold his son’s books and drawings. His son took him to court, and left him to languish in debtor’s prison whilst the young Cameron left for Russia. The memory of this lasted many years and in 1791 he was refused membership of the recently formed Architects’ Club. How he was invited to go to Russia is not known exactly, it is thought that his book might have secured his reputation overseas, but there were also rumours of an affair with the daughter of Isaac Ware, which could have caused him to leave the country in disgrace.

It is understood that Cameron was invited to go to Russia to work for Empress Catherine of Russia. Catherine was extremely well read, particularly in the classics. She amassed a large number of folios filled with exquisite engravings and studied architectural style, so understandably, she wanted her building commissions to reflect her fine taste. In order to ensure the quality of his builds, he arranged for Scottish craftsman to go to Russia. In only a few years, he had designed and had built a neo-classical gallery at the Summer Palace. His greatest work, the Palladian Pavlovsk Palace was to follow soon after. By 1779 he was in Russia and was glamorously described by Catherine as 'Mr Cameron, 'écossais de nation, Jacobite de profession, grand dessinateur, nourri d'antiquités, connu par un livre sur le bains romains'. For many years Cameron was a court architect in Russia, and much celebrated as an architect of great ability.

Charles Cameron (1730s-1812) Draft for the Dining Room in Catherine Palace - Photo: © http://www.arthermitage.org/

He is remembered in Russia as an architect who aside from his neo-classical designs, also pioneered the Greek Revival in particular the Greek Doric Temple of Friendship, 1780, at Pavlovsk. He is also known for the dome of the Cathedral of St Sophia which was the earliest first of the Byzantine revival style in Russia. Cameron also encouraged the Chinese taste in Russia inspired by the work of Sir William Chambers. He combined an enthusiasm for classicism with the taste for English Palladianism. Despite the fact that in Britain, we have hardly any records relating to his work, in Russia, his work is kept in major collections. His work can be found in the Hermitage, the Academy of Fine Arts Museums, the Museum of Pavlovsk and the Museum of Architecture.

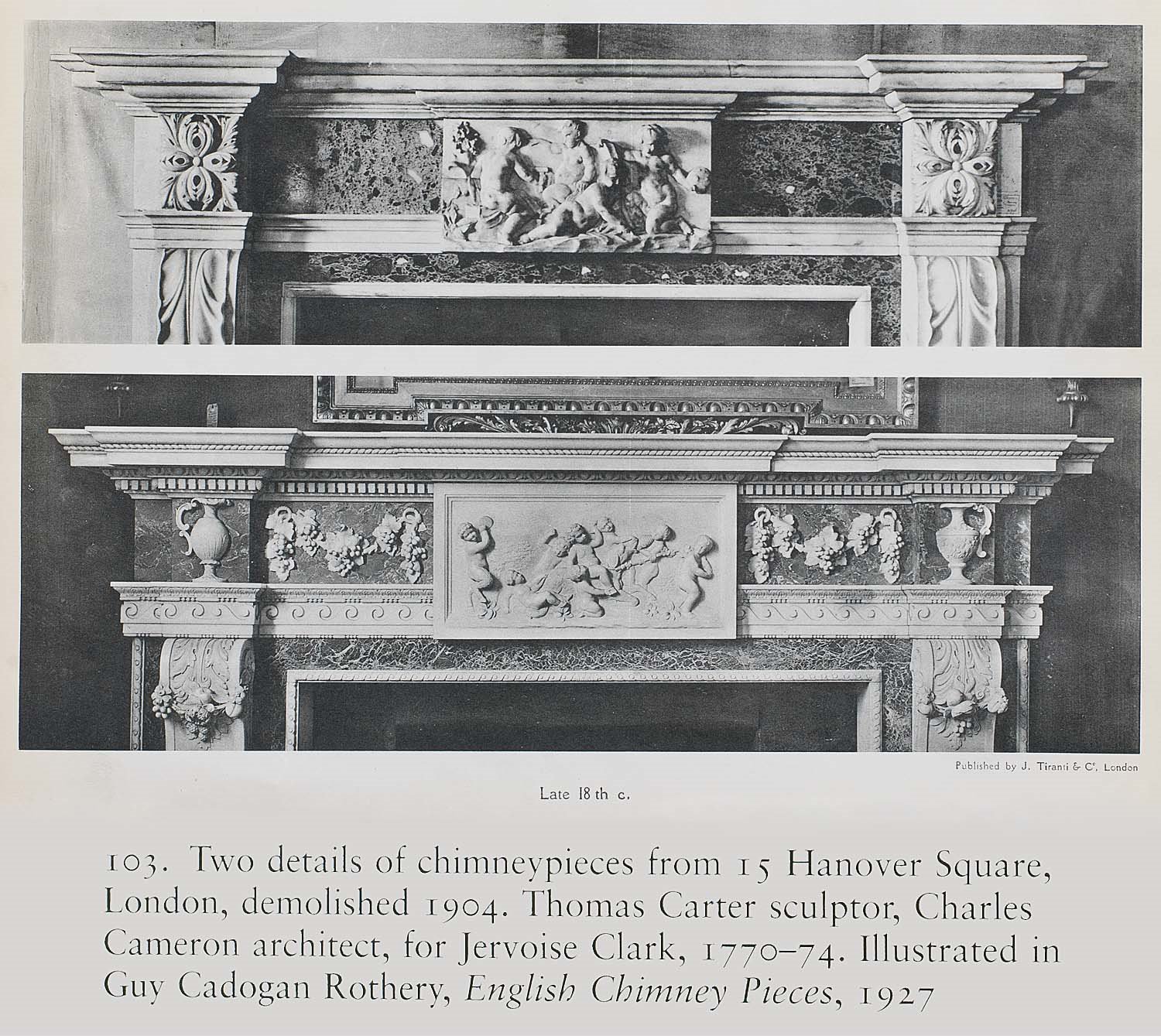

Cameron remains one of the greatest exponents of British taste and British Art abroad, yet his work on 15 Hanover Square has been lost over time, a victim to London’s ever evolving streets. Yet all is not quite lost. A chimneypiece designed by Cameron and made by the renowned sculptor Thomas Carter for this property still survives. This chimneypiece was almost certainly designed for one of the principle rooms in the house. The statuary marble chimneypiece is boldly carved, uniting both neo-classical and Palladian ideals to create an ornate yet elegantly balanced piece. The central tablet is carved in high relief with a depiction of putti representing the Arts, Sciences, Knowledge and Industry. This is centred on the frieze beneath the wide breakfront shelf. It is in turn flanked by a pair of large stylised foliate endblocks which sit above the sweeping console jambs.

The chimneypiece was taken out of 15 Hanover Square when it was demolished in 1904 and was subsequently promoted by prominent antique dealers of the time among them Mr Pratt, Messrs Keeble, Gill & Reigate & Sir Charles Allom. It was Illustrated in English Chimneypieces by Guy Cadogan Rothery and published by John Tiranti in 1927 and also in John Harris', Moving Rooms.

Please see some further images of this remarkable survival below.

If you would like any further information about this piece, do not hesitate to contact us. For further pieces in our neo-classical collection, please see here.